Chapter 1

The Early Days of Borax and Ryan Through 1931.

Before the story about Ryan can be told it is important to know why Ryan was there in the first place. What was going on back then and why was that activity so important. That can be answered with one word. Borax.

Borax, which is also called sodium borate, sodium tetraborate, or disodium tetraborate, is a very important boron compound. It a mineral and a salt of boric acid and a soft colorless crystal that dissolve easily in water.

There are many uses for Borax. It is in detergents, cosmetics, and enamel glazes. It is also used to make buffer solutions in biochemistry, as a fire-retardant, as an anti-fungal compound for fiberglass, as a flux in metallurgy, neutron-capture shields for radioactive sources, a texturing agent in cooking, and as a precursor for other boron compounds.

The word borax is Arabic and borax was first discovered in dry lake beds in Tibet and was imported via the Silk Road to Arabia. Borax was first produced commercially in the United States between 1864 and 1868 in California at Clear Lake north of San Francisco. In 1874 large borax deposits were located in Saline Valley, California and minor production began at Searles Lake in San Bernardino County Calif.

In 1881 borax was discovered in Death Valley by Aaron Winters. Winters sold his claim to William T. Coleman, a prominent San Francisco businessman. A year later Coleman opened the Harmony Borax Works in Death Valley and began shipping borax out of Death Valley by way of the famed 20 Mule Teams.

Also in 1882 prospectors discovered a new borax ore on the south side of Furnace Creek Wash in the area of Monte Blanco and Corkscrew Canyon in Death Valley. This new ore was named “colmanite” in honor of borax developer William T. Coleman. These claims were bought by Coleman in 1883 and patented in 1887.

William T. Colman started to have major financial troubles in 1888 and the Harmony Borax Works closed and never reopened. Coleman’s troubles continued and in 1890 Coleman sold his holdings to Francis Marion “Borax” Smith, a very successful borax prospector from Teel’s Marsh, Nevada. Smith consolidated his properties with those of Coleman’s and created the Pacific Coast Borax Company.

One of the properties Smith acquired from Coleman was in the Calico Mountains of San Bernardino County. This location contained a large deposit of borax and Smith built a mining camp there and named it “Borate.” While Smith concentrated his mining efforts in Borate the claims in Death Valley were placed in a reserve status and only the assessment work was completed to retain the claims.

In 1899 Smith partnered with some British associates and formed the Borax Consolidated, Limited in London. Borax Consolidated became a holding company which then became the owner of the Pacific Coast Borax Company.

With the borax deposits nearing exhaustion in the Calico Mountains in 1903, the company started to look for a new source of ore and revisited their reserves near Death Valley.

Back in 1884 prospectors located outcroppings of colemanite east of the Greenwater Range, east of Death Valley. This new discovery was in the Amargosa Valley west of the Amargosa River. The claim became known as the Lila C Mine named at the time by its owner, William T. Coleman after his daughter, Lila C Coleman.

In 1907 Francis “Borax” Smith started mining operations at the Lila C Mine. But the mine was over 120 miles from the nearest railroad. Smith and his business partners decided to build a railroad to service the mine. This new railroad also held the potential to tap in to freighting services in the booming gold and silver mining districts of Goldfield, Tonopah and Bullfrog, Nevada.

Smith assigned his top field engineer, John Ryan, to build a railroad to the Lila C Mine. After some initial problems with the original route for the railroad Smith decided to build the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad north from the Santa Fe line at Ludlow, California.

Grading began on the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad in 1905 and the line was completed all the way to the Lila C late in 1907. The line ran for 121 miles from Ludlow to Death Valley Junction. Once the railroad reached Death Valley Junction work on the main line stopped and a branch was constructed 7 miles out to the Lila C. After that was completed work on the main line was continued and the track eventually ran to Beatty, Nevada.

The original settlement name of Lila C was changed to Ryan, in honor of John Ryan, Smith’s field engineer. The post office in Ryan opened the same year.

The borax deposits in the Calico Mountains gave out and the company quickly transferred operations to the Lila C Mine. Many of the wood buildings that were used at Borate were moved to Ryan.

The annual ore production of the Lila C far exceeded expectations. But Francis Smith knew that it would eventually run out and assigned John Ryan to begin reviewing the other claims.

John Ryan studied the claims at Monte Blanco and Corkscrew Canyon west of the Lila C and south of Furnace Creek Wash. Survey crews searched for routes for a railroad line to service the claims. But the route required for production at these claims would not be nearly as easy as the line across Amargosa Valley to Ryan. This line would ascend around the north end of the Greenwater Range and then they would need to locate a grade through Greenwater Valley to the north end of the Black Mountains of the Funeral Range in order to reach the claims.

The route of the new line went through a group of six borax claims on the west side of the Greenwater Mountains. These claims were located by Coleman’s prospectors in 1883 and 1884 and were called the Played Out, the Biddy McCarthy, the Lower Biddy McCarthy, the Grand View, the Lizzie V. Oakley and the Widow. There was sufficient ore in these claims to sustain production for many years before there would be a need to extend the railroad to the Monte Blanco and Corkscrew Canyon claims.

In 1913 the final route was surveyed for another branch of the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad to the six borax claims. The Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad was denied its request to increase capitalization for the new line by the California State Railroad Commission.

Borax Consolidated then formed its own railroad company and would build the line to the claims itself. The Death Valley Railroad was born in 1914 and it was decided that it would be a narrow gauge and would reuse some of the equipment from the Borate and Daggett Railroad used for the borax mines in the Calico Mountains.

The new narrow gauge track for the Death Valley Railroad would be placed inside the Tonopah and Tidewater standard gauge tracks from the Death Valley Junction to a point 3 miles out toward Ryan and the Lila C. From there the narrow gauge tracks would branch out for the run to the claims 15 miles northwest of Ryan.

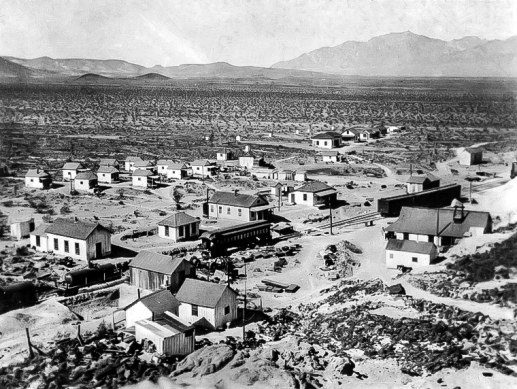

The 17 mile Death Valley Railroad was completed to the Biddy McCarthy mine in December 1914. The company removed the buildings from Ryan and located most of them on the slope adjacent to the Biddy McCarthy mine. Buildings originally built for use at Borate had been moved to Ryan and were now used in the new location next to the Biddy McCarthy.

The company named the new base of operations “Devar” which was a cleverly chosen acronym for the DEath VAlley Railroad. In 1920 the U.S. Geological Survey made a mistake while updating the Bullfrog Mountain quadrangle map and labeled Devar as “Devair” on the map. It was eventually decided to change the name of Devar to Ryan after the original settlement at the Lila C. This was also done to resolve complaints from the United States Postal Service. At first the Ryan settlements were referred to as Old Ryan and New Ryan. Eventually New Ryan was shortened to Ryan and Old Ryan referred to the site at the Lila C.

Just as New Ryan was being establish at the Biddy McCarthy mine, Francis Smith’s financial empire had collapsed. Smith had greatly overextended his real estate and electric railway investments and resigned from the Pacific Coast Borax Company.

Ryan sat in the close proximity of the six borax claims. The Played Out was two miles north on the railroad line and immediately south was the Biddy McCarthy and the Lower Biddy McCarthy. A little farther south was the Grand View, the Lizzie V. Oakley, and the Widow mines.

In 1915 the company started construction on an inexpensive two-foot gauge railroad dubbed the “Baby Gauge.” The Baby Gauge was built to service the mines south of Ryan and by 1918 the line had been extended to the Widow mine four miles south of Ryan.

This small railroad operated with gasoline engines pulling ore cars that could each carry three tons of ore. The Baby Gauge ore cars brought the borax ore in to Ryan and the small ore cars were pulled up on top of a large wood ore bin into which the ore was dumped. The ore in the large wood bin was then dumped into the narrow gauge hopper cars of the Death Valley Railroad. The DVRR would then haul the ore to Death Valley Junction for processing and final shipment on the Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad.

Baby Gauge cars loading ore to the DVRR Gondolas from the Widow Mine – Courtesy National Park Service, Death Valley National Park

Despite efforts by the International Workers of the World, Ryan was a non-union camp and remained that way until the mines shut down.

To help improve conditions at Ryan the Pacific Coast Borax Company purchased an old Catholic church in Rhyolite. The company moved the church to the northeast corner of Ryan and converted it to a recreational hall complete with a reading room. A stage was eventually added so the hall could serve as a theatre. Silent films were shown often in the hall and a piano and a violin would provide the musical score.

Of the known 100 borate minerals 25 are found in Death Valley. The primary commercial borate ores were borax, kernite, colemanite and ulexite. The ores mined at Ryan were colemanite and ulexite. While the company was building the railroad to Ryan it moved a processing mill from the Lila C to Death Valley Junction to separate out the borates in low-grade ore. The high-grade ore was shipped by rail to refineries at Alameda, California and Bayonne, New Jersey. The company also built a wet-processing plant and a Stebbins dry-deshaling plant at Ryan to solve ore processing problems.

The living conditions at Ryan were in need of many improvements. After four bug infested cabins that had originally come from Borate accidentally burned down Pacific Coast Borax quickly built new upgraded fireproof dormitories and 12 modern cottages for staff members and their families. Everything the company built had an industrial style to it. Even the small school building had the walls and roof clad in industrial corrugated metal. A sewage system was installed and better drinking water was imported by railroad tank cars from a well near Shoshone.

By 1928 the Pacific Coast Borax Company had developed vast new reserves of a new kind of borate ore in the Kramer District at Boron, California. The new ore called rasorite was less expensive to mine, transport and refine than the borates of the Death Valley region. The Played Out mine at Ryan finally lived up to its name and the Biddy McCarthy and Lower Biddy McCarthy mines were close to exhaustion. But the Widow mine proved to have vast deposits when it was originally believed to only contain a modest amount of ore.

Ryan’s output could still not compare with the output in the Kramer District. In 1928 the Pacific Coast Borax Company closed the mines at Ryan and placed the remaining ore deposits back in reserve status. The Death Valley Railroad would never resume construction down Greenwater Valley to Monte Blanco and Corkscrew Canyon.

At the same time Pacific Coast Borax was shutting down the mines at Ryan they decided to venture in to the tourist business. Improvements and accommodations were made to the old Greenland Ranch and it was renamed Furnace Creek Ranch. At the top of an alluvial fan southeast of the ranch the company built the Furnace Creek Inn. The community center at Death Valley Junction was turned in to the Amargosa Hotel and dormitories at Ryan were converted in to the Death Valley View Hotel. Views from the hotel offered visitors a sweeping vista of Furnace Creek Wash and Death Valley.

The Death Valley Railroad purchased a Brill motor car to transport visitors from Death Valley Junction to Ryan. The Tonopah and Tidewater Railroad also purchased a motor car to carry tourists from Ludlow to Death Valley Junction. The Pacific Coast Borax Company added seats to four of the Baby Gauge flat cars allowing the small mine train to carry tourists along the scenic mine railroad route to the Widow mine. Pacific Coast Borax partnered with Union Pacific Railroad to promote tourism to Death Valley and each company published colorful pamphlets to advertise the adventure and travel opportunities.

Black Thursday arrived in the fall of 1929 and the stock market crash brought on the Great Depression which abruptly ended the tourist boom. The Death Valley View Hotel and the Death Valley Railroad were shut down for good.

In December 1930 the Death Valley Railroad filed an application with the Interstate Commerce Commission to abandon its 30 mile narrow gauge railroad linking Ryan and the Death Valley Junction. In March 1931 the Death Valley Railroad ceased operations for good. The railroad was dismantled and was shipped along with its employees to Carlsbad, New Mexico where it operated for many years as the mine railroad of the United States Potash Company, a Pacific Coast Borax subsidiary.

Timber from a large trestle on the Death Valley Railroad line to Ryan was used in the beam framing for the bar at Furnace Creek Inn and DVRR Locomotive Number 2 was later placed on display at the Furnace Creek Borax Museum.

August 29, 1931 at the age of 85 Francis Marion “Borax” Smith passed away in Oakland, California.

(Please notify author on the website contact page for errors, omissions or suggestions.)

Reference sources and recommended reading:

- Gordon Chappell, Ryan, California – The Curious Case of the Portable Borate Mining Camp Near Death Valley (National Park Service, Western Region 1989)

- Gordon Chappell, The First Ryan: A Borate Mining Camp of the Amargosa (Proceedings Fourth Death Valley Conference on History and Prehistory 1995)

- Gordon Chappell, The Mining Camp of Borate and the Borate & Daggett Railroad 1890-1907 – An Interlude in the Borate Mining of the Death Valley Region (Proceedings Fifth Death Valley Conference on History and Prehistory 1999)

- Harry P. Gower, 50 Years in Death Valley – Memoirs of a Borax Man (Inland Printing & Engraving Company 1969)

- Linda W. Green & John A. Latschar, Death Valley National Monument – Historic Resource Study – A History of Mining (National Park Service 1981)

- Richard E. Lingenfelter, Death Valley & the Amargosa (University of Calif. Press 1986)

- Robert P. Palazzo, Railroads of Death Valley (Arcadia Publishing 2011)

- Mary Ringhoff, Life and Work in the Ryan District, Death Valley, California, 1914 – 1930: A Historic Context for a Borax Mining Community (Thesis, ProQuest 2012)